Still Struggling: A Cambodian Community's Assessment and Response to Long-Term Negative Effects of Involuntary Relocation.

|

BANKWATCH -OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF NGO FORUM ON ADB- March 2021 |

|

|

Leakhana Kol | |

|

||

|

US$4,500 |

Research Background Final Report (abstract) Others

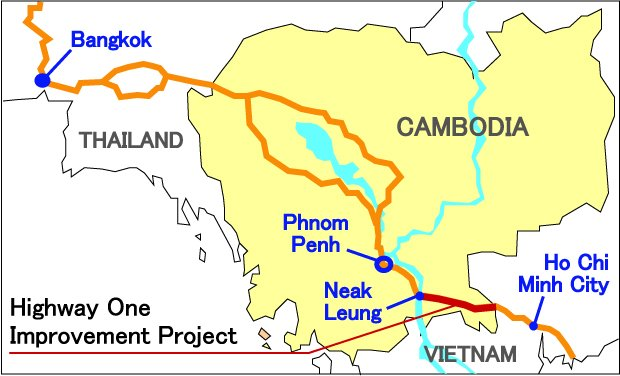

Research site map (c)Mekong Watch

Community Pump well in Stung Slot Community

Research Background

As in many other developing countries, involuntary relocation of local communities, often caused by large-scale development projects, e.g., road expansion, is practiced in Cambodia with inadequate consultation and compensation for affected people. It severely impacts local communities, leading to long-term livelihood and life challenges for them. However, negative consequences of involuntary relocation of communities are not sufficiently recognized, let alone seriously addressed, by policy-makers, government workers, and the public in Cambodia.

This research tries to fill in such a gap by documenting long-lasting effects of development-induced relocation experienced by a small suburban community, Stung Slot, located near Neak Leung, southern Cambodia. Sixty-three families in Stung Slot were resettled in the early 2000s due to Highway One Improvement Project funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The Stung Slot community is still struggling to recover from the relocation impacts after almost 20 years.

The documentation takes the form of citizen science, i.e., participatory action research, involving a number of community members, including community researchers trained by the principle investigator. It is also sensitive to women's voices and ensures their active participation in data collection, analysis, and reporting. Both quantitative and qualitative data are gathered through structured interview and focus group discussion with the purpose to provide an overall profile of the relocation effects currently facing the Stung Slot community.

Structured interview is carried out by up to five community researchers, which helps raise awareness of both interviewees and interviewers over the resettlement impacts. Each focus group discussion invites around seven families, including community researchers, soliciting the participants' collective and contextualized narratives on their relocation experiences, which may not be well captured in structured interview. Focus group discussion is also expected to stimulate ideas on what Stung Slot as a community should do for the future.

Evidence on the long-term relocation effects and challenges facing the community is likely to cover a wide range of topics, including housing/land issues, basic human needs such as clean water, food security, and healthcare, children's education, livelihood and cash income, non-performing debts, economic migration, seasonal flooding, trespassing of squatters, as well as problems more specific to each family, e.g., alcoholism, gambling, DV, HIV, and disability.

The research results are disseminated among policy-makers, government officials, development experts, corporate representatives, NGOs, and general public both through the conventional media and social media to make them realize risks of relocating local communities, especially those who are economically and socially vulnerable. For the Stung Slot community, the research is an important step to understand, discuss, and address the outstanding resettlement effects to restore themselves, including finding ways to outreach and reunite the families who have migrated from the community.

The community research team is also eager to share their experiences with other communities in Cambodia and elsewhere who are facing similar development-induced involuntary relocation. They are hoping that international NGOs can help them access other key actors, in particular ADB officials and donor governments, so that they can raise issues with them as well.

[Sep. 2019]

Final Report (abstract)

Plese see the full report from here.

The goal of this participatory action research was to document the long-term effects of development-induced resettlement experienced by Stung Slot Community (SSC), located in Prey Veng province, southern Cambodia. Sixty-three families were involuntarily resettled in the early 2000s due to the Highway One (HW1) rehabilitation project, financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The research team used household surveys (HHS) and focus group discussions (FGD) as the main way to systematically collect data. The team also conducted observations of the resettlement site and elsewhere in the HW1 project area.

The results of the data collection in Stung Slot Community and review of the community profile show the HW1 project's long-term negative impacts on the SSC families:

1) A significant proportion of the SSC families (19.0%) is still self-employed, engaging in home-based work, waste collection, driving a cyclo or a tuktuk, small businesses, and trading, as they were before they were relocated. Since relocation, slightly more people (14.0%) engage in unskilled daily-waged labour, skilled labour, and housekeeping. This seems to indicate that the HW1 project has not significantly changed the SSC families' livelihood means;

2) The proportion of housewives has decreased considerably (24.0%) as compared to the pre-relocation stage (33.0%), while the families who rely on remittance from family members' migratory labor has more than doubled to 14.0%. This indicates the SSC families' increased difficulty accessing opportunities to earn cash income in the HW1 project area;

3) The SSC families' average monthly income has returned to the pre-relocation level, which is about 100.00 USD. On the other hand, a gap between the households who earn more and those who earn less than the average has widened;

4) More than half (56.0%) of the survey respondents have children under 18 years old in their households, but 44.0% stated that their children do not attend school regularly. Major reasons for parents' not sending their children to school regularly include: Schools are far from home, they need their children to work to help earn family income, and they have no money to pay informal fees to teachers;

5) While a good majority, around three-quarters, of the SSC families seem to have someone in their household with health problems, only a small portion has ever been registered as an ID Poor Household. Of these households, only 5.0% have actually received free health services;

6) Some SSC families have yet to install a flushing toilet at home: 71.0% use a toilet at their neighbors' house and 16.0% a toilet in an abandoned house. Many have no access to garbage services: 65.0% said that they throw garbage on vacant land/rice fields and 4.0% bury it in the ground; and

7) Only 7.0% of the survey respondents said that they can afford three meals a day: 62.5% felt that they have no secure access to food; 49.0% supplement their income by collecting things such as fish, water lily and other aquatic products from local streams and lakes for their own consumption; and 5.0% eat only rice with little vegetables or meat and borrow money to buy food.

After more than 20 years, the SSC families are still struggling to recover from the project's resettlement effects. The SSC case shows how involuntary resettlement, especially when it is mismanaged initially, can impact vulnerable communities over a long period of time. During FGD with the SCC families, the following actions were suggested to help address the challenges of the community:

1. Collectively rent a space in the local market to sell goods and products and invest in the agricultural sector by renting farmland;

2. Encourage the members who owe the community savings group a debt to return the money, with which to reactivate the revolving fund to support both existing and new jobs;

3. Focus first on ways to resolve land disputes with the squatters on the resettlement site, for instance, by asking authorities to approve a social land concession for the squatters. Then start reorganizing the community to make other improvements to community infrastructure and initiating livelihood enhancement programs;

4. Contact school principals and ask them to provide scholarships and other support to the children from the SSC families;

5. Involve more male members in the community committee to integrate their views and support into community activities;

6. Outreach to groups of farmers, middle-men, retailers, and buyers to establish a network of producers, transporters, and consumers of SSC goods and products;

7. Clean the resettlement site together by installing rubbish bins, planting more trees, and helping the SSC members reduce the amount of waste they produce daily; and

8. Carry out more detailed research on SSC's food security and safety to learn how to improve health conditions of the community members, especially children, the elderly, and members with disabilities.

[Apr. 2021]

Others