Introduction

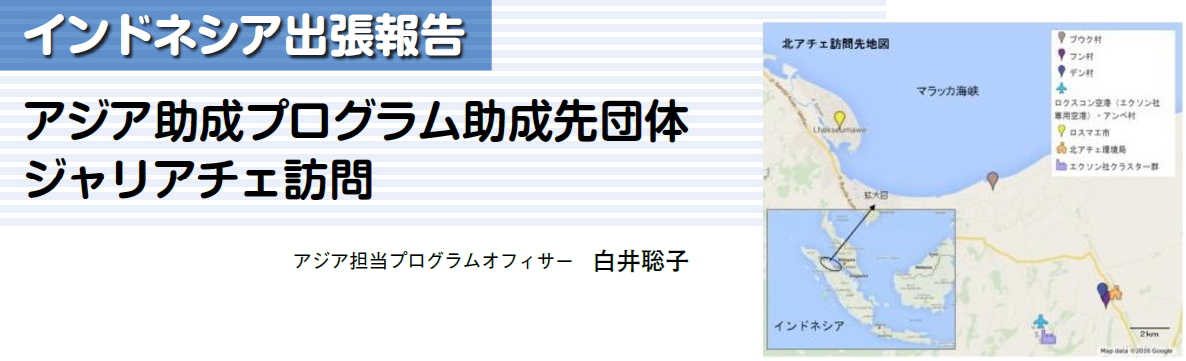

The Takagi Fund for Citizen Science has funded Jari Aceh, an Indonesian women’s rights organization from 2012 to 2014, and in 2015. I had the pleasure of visiting them on March 10-14, 2016 for the review and follow-up of their sponsored project, an analysis of the environmental damage caused by natural gas excavations on Exxon Mobile’ Oil Co.’s site in the North Aceh prefecture.

Consultations with our grantees and the local government, as well as terrain observation, allowed me to grasp the series of events that led to today’s situation. I was able to help our grantee’s research by measuring mercury levels in hair samples from the local population (restricted to the population within the site of interest).

During my visit, I received the invaluable support of Ms. Natsuko Saeki from the Network for Indonesian Democracy, Japan (NINDJA), who acted as interpreter and local coordinator. Our hair sample analysis could not have been conducted without the help of Mr. Kunio Endo, a board member of Minamata Disease Museum/Soshisha and Takagi Fund’s former selection committee member (2011- 2014), and Mr. Koichi Haraguchi, a chief investigator from the Department of International Affairs and Research, National Institute of Minamata Disease. I would hence like to take this opportunity and thank all of the above-mentioned persons, whose support we highly appreciated.

March 10th, Arrival & office visit

After leaving Narita Airport and going through two layovers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and Medan, Sumatra Island, we eventually reached Lhokseumawe Airport in Aceh state, North Aceh Prefecture.

Peeking through my cabin window just before landing, I could see Arun NGL’s white gas tanks along the coastline (the company liquefies and stores natural gas, as can be seen in photo 1 and the typical Indonesian landscape inclusive of palm trees, rice paddies and wooden houses spread out around the outer edge of this scenery (Arun has now transferred its operations to Prutamina, the state-owned petroleum corporation).

While we were driving from the airport to the city, we passed by a unusual place. Nasuko explained this was the area where residents expropriated by Arun when the company constructed the plant re-settled in “temporary houses,” along the road we were on. Since then, they have engaged in a number of strikes, asking for return of the land. They knew that Arun would eventually withdraw from the area once natural gas resources were exhausted. (see photo 2) Arun’s facilities were built thanks to a Japanese natural gas development loan (1974).

These “temporary houses”were constructed nicely and firmly, compared to the local housing standard. As we passed through, children were playing outside rambunctiously, and cows were resting in the alleys between houses. Looking at this peaceful scene, I realized I couldn’t have guessed the struggles of its inhabitants, had I not be given an explanation by our guides.

We then arrived at Jari Aceh’s office and had a meeting regarding our schedule from the next day, including hair sampling preparation. I also interviewed them about the current status of funded projects, the status of their ongoing project, and the future outlook of all these initiatives. (see photo 3)

|

|

|

|

|

|

March 11th, Interview of North Aceh’s regional Environment Bureau, and inspection of Exxon’s old factory site and related facilities.

In the morning of March 11, we visited North Aceh’s regional Environment Bureau for a meeting with Ms. Nuruaina, the Bureau Chief (see photos 4 and 5). She mentioned that operators must not leave the site without going through decontamination, and that with regard to Exxon’s old excavation field, an expert team from the Ministry of Environment in Jakarta had been dispatched to decontaminate the soil. They had then requested an academic institution to monitor the area. According to the institution, no health issue had been reported by residents so far. My impression was that the government deemed the issue solved. Ms. Nuruaina explained that the regional bureau had jurisdiction over all kinds of environmental issues, but that its manpower was insufficient to tackle all of them. “People making money from natural resources think tackling environmental issues hinders them,” she continued. “We’ve even had cases where our inspection staff was greeted with hatchets at the entrance of the site. Our position as a regional bureau is weak, so we've asked Congress and a number of agencies for their support.”

Inthe afternoon,we visited Exxon’s facilities (the private airport, the old excavation sites, and the well where mercury is found) and the Ampe village, where our grantee reported that oily, polluted water flowed into the river and duck carcasses had been found. The excavation site had been guarded by the Exxon Corporation in 2012-2013, when the pond inside had been covered with a plastic sheet. The area was restricted at that time. After safety was confirmed, they withdrew from the site, and the public was allowed to enter again. Now, weeds overgrew most of the site,

and the place where the pond must have been located once had been filled with earth. The place seemed dried up, and here and there, the ground had turned black (see photo 6).

March 12th, Visit of Puk village and hair sampling

We arrived at Puk village by 10: 00 AM. This village is located along the coast and was severely damaged by the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake and tsunami. There were stalls selling fish at the entrance of the village and fishermen catching crabs in the mangrove forest, using traditional fishing techniques. Meanwhile, countless shrimp farms sat along the road all the way to the village.

About 20 people gathered in the building where hair sampling was performed. Most of them were middle-aged and elder men who had complained of poor health, mainly skin problems.

Before starting the sampling, Jari Aceh explained the purpose of our visit to the small audience. Then we started working and collecting samples from those who wished to know the mercury concentration in their hair (Photo 7). Once participants had their hair picked, the staff interviewed them, asking for personal information about their lifestyle and living environment (such as name, age, amount and frequency of fish consumption, use of UV cream and perm solution).

|

|

|

|

|

|

March 13th, Visit of Funh & Denh villages and hair sampling

That day, we visited Funh Village in the morning and Den Village in the afternoon. Both villages are located further inland from Puk, which we had visited the previous day. In between the two villages are the regional Environment Bureau and Exxon’s excavation site, which we had explored on the 11th.

Strikingly, Hung Village had a completely different atmosphere from Puk Village’s. The villagers who gathered in the meeting area were relatively young, and we counted many women and children. Sweets and drinks were served so that it seemed more like a local gathering. (Photo 8).。

I then visited Den Village in the afternoon, where a wedding ceremony was taking place. As a result, few residents gathered at the meeting point, except for the family that had offered to host the gathering (Photo 9). However, since Hun and Den Villages are close by, and dwellers’ lifestyles are similar, I decided to combine the hair sample data. Hair sampling was performed following the same protocol as the previous day’s. We completed our tasks nearly as scheduled, and I returned to Japan the next day.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The results of our hair sample analysis

After returning to Japan, I mailed the 40 hair samples we had collected along with the questionnaires filled by participants to the National Institute for Minamata disease. Their analysis found a mercury concentration in sampled hair lower than that found in gold miners and even in the Japanese population. A limitation to these results is the fact that sampling participant selection had not been coordinated in advance to ensure proper comparability between our participants and the general population, and between several geographical areas. Nonetheless, our present results do not confirm any contamination by mercury in the local population.

In North Aceh, we faced a situation where the company responsible for local pollution was clearly identifiable, and where the presence of mercury, as well as its effects on the local population that came in contact with it, were visible to the naked eye. Despite this, the results from our hair sample analysis could not confirm any quantifiable damage to residents’ health. But unfortunately, this does nothing to alleviate health concerns locally or to improve the noticeable pollution in the region. This discrepancy between the situation on the ground and our results calls for a deepened investigation into the state of North Aceh’s environment and the influence that Exxon Mobile’s plants may have had on it. We must keep on honing our understanding of how economic development impacts environmental and social systems.

Closing Remarks

When hearing “Aceh,” many think of the Sumatra earthquake and tsunami in 2004. However, few people know that a civil war occurred in the area before that, as a result of which foreigners were not allowed to enter the region. Ironically, it is the earthquake that triggered the re-opening of the area to the outside world, in the form of accepting disaster relief.

In the background of this tragic civil war stood the exploitation of North Aceh’s rich natural resources and Indonesia’s economic development. The benefits of this development were not redistributed to the local people; on the contrary, those consistently flowed outside the region. An independence movement formed, but was suppressed through human rights violations, torture and mass killingsーall in the name of political stability. And Japan’s indirect complicity in these events is another fact known by few.

Behind the scene of the tragic civil war, there was a situation the country was pushing ahead economic development over the rich natural resources in north Aceh. The local people, rather than the benefit from the development was not distributed to the people in the area but most of them flowed outside. Rather, the independence movement was suppressed. Human rights violation, torture and slaughter occurred to suppress the independence movement in the name of political stability.

In the book Voices of Aceh: War, Daily Life and Tsunami (Natusuko Saeki, Commons, 2005), we can read that "Japan, which relies on Indonesia for most of its natural gas imports, has built natural gas plants through ODA since the 1970s. Under the pretext of protecting Japan’s energy security, Indonesian armed forces are stationed at Arun corporation where local people have been interrogated, tortured and massacred.” The Exxon issue itself is a major environmental problem, but I do think that we, as Japanese, need to know it was also historically linked to such serious human rights violations, and that we have consumed “bloodied” natural gas unknowingly.

Another thing I noticed is the "Aceh" we know is in most cases the area around Banda Aceh, the provincial capital, which has been rehabilitated and developed thanks to international aid following the earthquake disaster. On the other hand, the North Aceh Province, which I visited this time, could be called "Another Aceh." This remote area far from the region center has received very little external support. Looking at soft development aspects such as human resources development and educational environment, we see that the region clearly lags.

Having said that, it is hard to imagine from my visit that a brutal civil war occurred in the region just twelve years ago. I didn’t see any hints of this tragic event during my stay, and it felt like visiting any other Indonesian locality.

After staying a few days in Aceh, I still have countless things to learn about the local history and culture, but I was able to deepen my understanding of the project and its complexity by witnessing its evolution and interacting with local residents. It was a good opportunity for Jari Aceh since they were able to obtain scientific data for the first time, thanks to hair sampling and analysis, which provided them with some answers as to whether health damage has been caused by mercury. In reality, hair sampling had been conducted in the past, but nobody knows who conducted it and what the result was.

So our survey was a valuable opportunity for local residents who have grown distrustful of any exterior intervention.

Once again, I would like to express my gratitude to Jari Aceh for welcoming me and share my sincere respect for their committed endeavors. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to all those who have helped coordinate my visit.