Introduction

|

From July 23 to 27, 2017, I went to Mongolia to visit one of our grant recipients, the Mongolian Sustainable Development Bridge (MSDB), whose research focuses on assessing "public awareness of Mongolia's mining sector's water management and radiation impact." The organization is carrying out social and environmental assessments around selected mining areas on its own, independently of any government or developer interference. They are also aiming at establishing Mongolia's first citizen science group as part of this research project.

It took four and a half hours to fly from Tokyo's Narita Airport to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia's capital. After entering mainland China, crossing a desert stretch followed by prairies, I eventually spotted the sparse Gers typical of Mongolian sceneries (traditional Mongolian mobile houses made from timber and wool), until suddenly modern buildings erupted from the horizon, and we arrived at the capital city.

My hosts explained that June and July are the best months to visit Ulaanbaatar, since the climate is pleasant and many city dwellers leave the city for the countryside to spend their summer vacation. As a result, we encountered few people and little traffic downtown.

|

The day following my arrival, I visited the MSDB office in the heart of Ulaanbaatar's business district, just a few minutes' walk from the Chinggis Khaan square. Three women welcomed me in the office. They said they were not environmental experts; however, they had studied abroad and/or worked at a multinational company. I realized they belonged to the global elite and that they were by far competent enough to conduct the required research. They also possessed a strong network, and this convinced me I was facing a strategic team. Most important, I could feel their passionate dedication to conserve the environment for future generations, a mission they had desired to pursue since childhood.

Walking around Ulaanbaatar

After our interview that afternoon, my hosts kindly offered to take me to a nearby hill where we could admire a panoramic view of the city. From there, the dynamism of the booming capital was obvious: as far as the eye could see, I could spot commercial and apartment buildings under construction and active thermal power stations, a scenery that certainly symbolized perfectly the current state of Mongolia. And most impressive, a section of the city populated by Gers.

In Mongolia, around 3 million people live in an area approximately 4 times as wide as Japan, making it the country with the lowest population density in the world. After the democratization of the 90s, Mongolians' lifestyle changed drastically and a large number of domestic animals died of Zodo (cold wave) due to the recent extreme weather, which led the nomadic herders to abandon their traditional nomadic lifestyle and flow to the city. Recent statistics estimate that about a half of Mongolia's total population live in Ulaanbaatar now.

In addition, approximately 60% of the city's population live in the Ger district that hosts immigrants and lower-income residents.

Since the Ger district is isolated from the infrastructure system controlled by the government, residents must burn lots of coal and wood in individual stoves during Mongolia's harsh winter, which is one of the main factors for severe air pollution in the city. Aside from the damage caused by rapid urbanization, Mongolia faces a number of environmental challenges such as desertification and frequent forest fires caused by dry weather as a result of climate change, with the latter declared a national emergency.

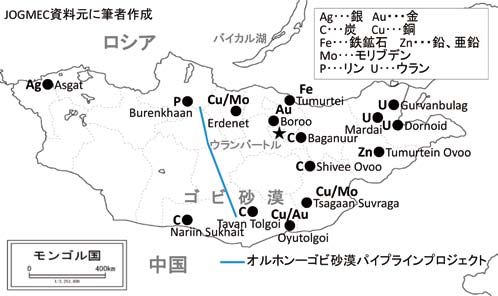

Mongolian mineral development and related environmental issues

|

|

|

|

|

Spreading the concept of "Citizen Science" throughout Mongolian society

One of the two pillars of this year's MSDB's projects, Citizen Science is a program whereby citizen themselves perform social and environmental assessments, independently from the government and corporations, and release the data publicly. Through providing citizens with information and raising public awareness, the program empowers people to require developers to revise or even stop the project investigated and/or negotiate with decision-makers. MSDB is currently establishing a reliable and independent website.

The "citizen science" they define is a series of activities that make the public have power as an interested party in solving society's most pressing issues brought about by modern science, technology and human activities. This, I believe, can be an effective tool to empower citizens to raise their voice. MSDB is eager to establish the first Mongolian citizen science group and spread the concept of "citizen science" through this subsidized project.

Conclusion

Mongolia attracts many people for its magnificent nature, and flocks of tourists have been drawn to the country, including Japanese. On the other hand, Mongolia's transformation into a country that relies heavily on natural resources has been dramatic. Some have said that Mongolia is going to be "the second Saudi Arabia" or that its "nomadic herders will swap their camels for private jets in 20 years."

Japan has very strong economic ties in terms of direct investment and exports into the country, following China, Russia and Korea in importance, and our government treats the steady supply of metallic mineral resources including rare metals as a diplomatic priority.

Now that the word "sustainability" has entered our vocabulary and that its use has become commonplace and natural, such as in "the sustainable and steady supply of resources" or "the sustainable development of mineral resources," we, as general citizens, have an important role to play in watching and evaluating policies to ascertain that they are truly "sustainable."

Mongolia just held its presidential election in July 2017. It seems that many citizens were hoping for a new president who would break away from the current trade structure whereby around 90% of Mongolian resources are exported to China, and who would invest in promoting local businesses.

In addition, the landscapes of Dauria were registered as a UNESCO world natural heritage in 2017 thanks to a joint application by Russia and Mongolia, and these valuable natural environments are located near the area where resource exploitation projects are being developed. This registration could be the spearhead advancing MSDB's activities, and we would like to give them our full support.

Last but not least, let me copy here a message from them. "Although we are a young group, the Takagi fund chose our project with high expectations and trust. We warmly thank the Takagi Fund and its supporters in Japan. "

|

|

|

Ms. Ulziibileg (the leftmost ) and her co-workers at MSDB office

Ms. Ulziibileg (the leftmost ) and her co-workers at MSDB office

The Baganuur coal mine and the diggings

The Baganuur coal mine and the diggings Gorkhi-Terelj National Park, the suburbs of Ulaanbaatar

Gorkhi-Terelj National Park, the suburbs of Ulaanbaatar